Gandhi's Charkha & Fukuoka's One Straw Revolution

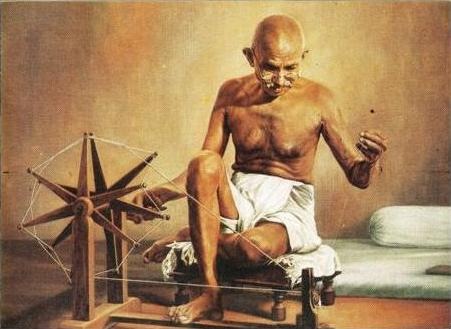

In the preface to the Indian edition of Masanobu Fukuoka's „The One-Straw Revolution“ Partap C. Aggarwal compares the power that may lie in self-reliant and low-tech agroecological methods with the symbolic meaning of Gandhi's spinning wheel - the charkha - which is a strong symbol of the Indian independence movement. This is the first time that I came to appreciate the term Revolution in this way, as related to the Straw:

„At Rasulia, my friends and I were also trying to find a whole new way of life which would bring us in harmony with the environment, life, people, ourselves. Agriculture was only a part within the whole. We had therefore no difficulty relating with either Fukuoka's ideas of unity of all things, or with his philosophy of do-nothing.

Of course we understood these ideas in our own way. Fukuoka reaffirmed our view to our great joy and satisfaction. In fact we too saw revolution in a straw. We did believe that if only a fraction of ordinary Indian farmers could adopt rishi kheti they could bring down the agro-business establishment, the government, and with it the entire urban-industrial structures in the country. Perhaps the straw had the same kind of power as Gandhi's charkha.“

(P.C. Aggarwal, 1994).

„At Rasulia, my friends and I were also trying to find a whole new way of life which would bring us in harmony with the environment, life, people, ourselves. Agriculture was only a part within the whole. We had therefore no difficulty relating with either Fukuoka's ideas of unity of all things, or with his philosophy of do-nothing.

Of course we understood these ideas in our own way. Fukuoka reaffirmed our view to our great joy and satisfaction. In fact we too saw revolution in a straw. We did believe that if only a fraction of ordinary Indian farmers could adopt rishi kheti they could bring down the agro-business establishment, the government, and with it the entire urban-industrial structures in the country. Perhaps the straw had the same kind of power as Gandhi's charkha.“

(P.C. Aggarwal, 1994).

The history of Gandhi's charkha (Source: http://www.charkhafiberbook.com/history.html):

"Until recently in India, women could not inherit real property. She was trained to be the perfect bride and must excel in domestic tasks to provide for her family such as cooking, cleaning and spinning. In rural India, rules were set up so that a man could not marry a girl from his own village, so when a girl got married, she had to leave her village. In order to compensate the girl for her share of the land, she was given a dowry when she married that would allow her to complete her duties as a wife, including large sums of cash, household items and a charkha. This charkha might be highly decorated if the girl came from a wealthy family. Women would spin as part of their daily routine and would often get together in groups to spin and socialize (much like a quilting bee in rural America). Cotton and silk both are traditional fibers spun on the charkha. They would weave cloth or rugs from their spun yarn.

When Gandhi came along, India was under British colonial rule. Cotton was grown in India where the men would harvest it and the British would ship this cotton back to England and have it woven and spun into cloth which was then shipped back to India and sold at a price that the people could not afford. In order to resist against the British, Gandhi encouraged the men to spin (which was traditionally women’s work) and weave their own cloth and wear clothing made from this homespun cloth. This cloth was called khaddar or khadi (meaning rough).

As part of the passive resistance movement, Gandhi would often spin in public. Since the traditional charkha was typically bulky and difficult to move, he needed a charkha that could be transported easily. He held a contest to design a charkha that would be compact, portable and affordable. The box design of charkha won that contest. Tradition states that the accelerator wheel was an idea of Gandhi’s."